Here is an exclusive video interview between Hans Ulrich Obrist and Tyler Hobbs to mark the final week of Hobbs’ debut UK solo show at Unit London.

‘Mechanical Hand’, Tyler Hobbs’ first solo exhibition with Unit London explores the interactions between man and machine, digital and analogue, and computer-driven and hand-made creations. Hobbs states that as our lives become increasingly digital ‘there is an imperative for artists to help us develop a healthy relationship with computers – to help us build beautiful things.’

Programming Meets Art

Typer Hobbs grew up drawing and painting since childhood, but his father steered him towards computer science – another interest of his – leading to a degree and programming career while creating art on the sidelines. The real game-changer was merging programming with art which felt unique and intriguing. Before he knew it, he found himself engrossed in generative art.

For Tyler it’s not only about being influenced by past artists, but interacting with their ideas. He mentions Agnes Martin’s focus on evoking particular effects or connections rather than intellectual backing as something which has significantly impacted how he creates.

While every artist working with computers influences him to some extent, Tyler also draws some interesting parallels to artists who didn’t use computers. Even they can be seen as using algorithms if you think of style as algorithmic process. Mondrian’s iconic style of black and white grids filled occasionally red, yellow or blue sections could be viewed as simple algorithm at play!

He constantly observes these artists attempting to decode their systematic approach behind their creations. This mode of learning led many influencers shaping how he makes his works. Considering the absence of formal education they were essential part of his self-training.

Reflections on Generative Art History

The Los Angeles County Museum (LACMA) has recently unveiled an impressive exhibition observing the history of computer art. This exhibit features pioneers in computer art from all over the world, including artists such as Manfred Mohr. This show serves as a tribute to these innovators and a protest against forgetting their contributions, particularly amidst today’s focus on digital art.

Tyler notes that his interest lies in creating more human-centric works that evoke warmth and understanding without being entirely dominated by technology. Artists like Casey Reas, who created tools that allow for this fusion to happen, have also inspired his personal style significantly.

Generative art can be described as creating systematic artwork or crafting it through a process rather than focusing solely on the end image itself.

There isn’t really one fixed approach; you could lean heavily towards using generative techniques or use them sparingly depending upon your preferences and artistic vision. In essence though, putting emphasis on working systematically allows you to bypass limitations set by your imagination alone.

Relinquishing Control

When asked about the process of giving instructions and promoting chance occurrences in a collection, the discussion moves to Tyler Hobbs’ project QQL.

QQL is a project where participants play an active role in executing instructions (like making a salad from a recipe). This approach echoes Duchamp’s idea that half the work is done by the viewer, making it highly participatory.

Tyler notes, that algorithmic art necessitate explicit instructions due to machines not being able to process ambiguous directives – even randomness must be carefully prescribed. To generate open-ended outcomes something like QQL comes into play, where individual steering or curatorial input becomes crucial.

Generative systems shift focus towards curation more so than creation.

An intriguing aspect of QQL is this absence of the artists curatorial influence; instead allowing natural chronological progression based on user choices over time.

The beauty of QQL is about observing how people evolve their interests within algorithm-based artworks overtime and watching them grapple with commitment issues similar to artists. Their choices are irreversible but contribute significantly to an outcome Tyler Hobbs couldn’t achieve alone through curation — leading to many unexpected yet intriguing results.

Creating Fidenza

Tyler Hobbs’ most notable work is Fidenza which was a significant step in his artistic practice.

Though it appears as an innovative creation, it’s actually built on elements from his earlier works. This is the beauty of working with code; you can easily reinvent and reuse parts to create something new. The foundation for Fidenza, essentially a flow field system, was devised by him in 2015 at a coffee shop on a sketch pad. However, the actual project didn’t materialize until 2021.

When he learned about Artblocks and NFTs along with generative artwork that’s encoded on blockchain platforms, he felt ready to develop Fidenza. He had been working with an algorithm that seemed perfect for this task, as it had the range and depth required for generating 999 outputs.

The control-chance oxymoron often seen in digital art applies here too; artists embrace randomness yet like keeping things controlled. In physical media like watercolor painting for instance, chance plays its part naturally since outcomes aren’t always predictable. With computers however, randomness isn’t inherent but needs to be explicitly programmed into the algorithms by artists who then gain richness in response as compensation for lost control.

Tyler notes that he used randomness strategically in many aspects of designing Fidenza including deciding color palettes or scales of elements among other attributes according to their relevance or interest level within the artwork so that nothing became repetitive.

Exploring Artistic Duality: Hand and Machine

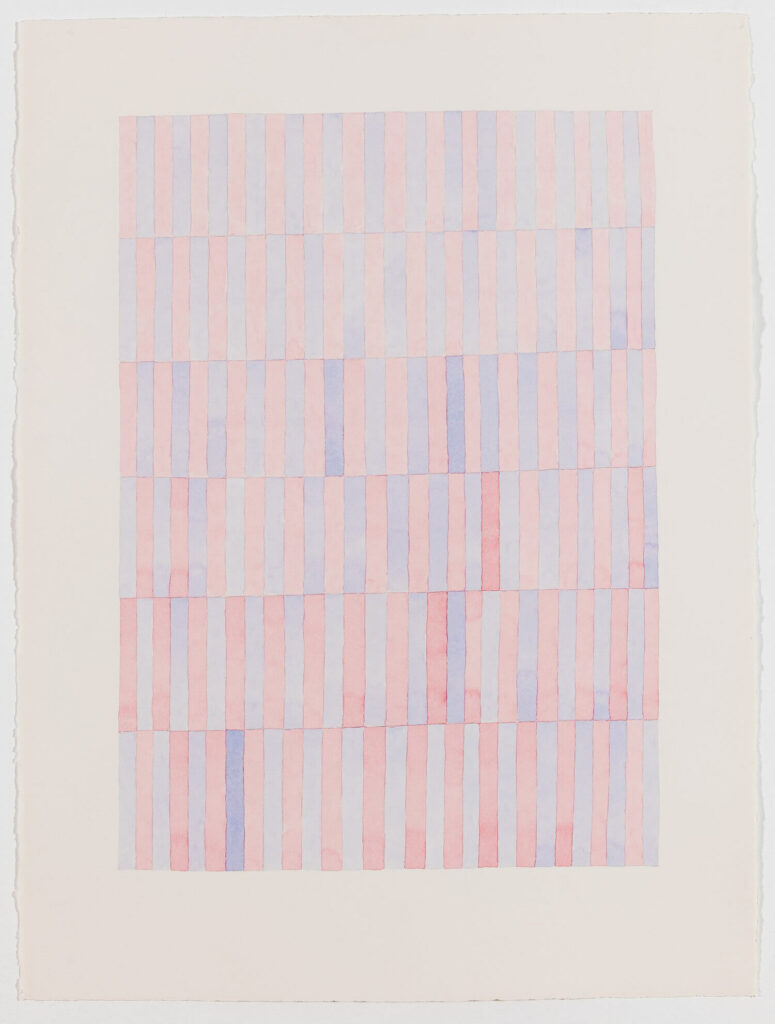

Using the watercolor example as transition, the focus shifts to the exhibition at Unit London and specifically Delicate Futures – a watercolor piece done entirely by hand.

Delicate Futures embodies Generative Art but beyond its current perception – it’s about creating work systematically with a procedural approach. Tyler Hobbs used his hands to create a simple repetitive structure typically associated with computers. However, using hands will always have unique characteristics or “flaws” such as uneven lines which make things slightly imperfect but interesting.

Fulfilling System addresses both hand and machine elements rather than choosing one over another. It has two graphite on paper works where he covered each sheet evenly – one by hand while the other via machine alone – revealing qualities of these different methods of creation.

Fulfilling System 1 clearly shows human touch due to many ‘mistakes’ our eyes and hands naturally commit like accidentally curving straight lines or subtly shifting pressures adding uniqueness to the artwork representing physical human traits.

On contrast, Fulfilling System 2 uses a plotter robot drawing vertical lines until it covers entire sheet exposing mechanical process flaws – leaving traces of motors, manufacturing details even including wood beneath paper – adding its own distinct ‘mechanical fingerprint’.

These two worlds come together in Jacquard Legacy combining everything into one canvas reflecting different aesthetics.

The interview took place against the backdrop of “By Proxy,” a key piece in the show. It’s unique because it merges hand-crafted and machine-made artistry, each doing what the other cannot. The artwork is made of graphite and chalk pastel on paper; graphite being executed by machine, while chalk pastel is drawn by hand.

The perfection found in straight lines or grids achieved with graphite just isn’t possible to replicate manually. A computer excels at these precise markings thanks to its consistency and precision. On the contrary, chalk pastel brings out freedom and character — qualities that come naturally when drawing with our hands but are nearly impossible for machines to mimic effectively. These two contrasting elements coexist harmoniously within his work, each highlighting their strengths through this juxtaposition.

‘Return One‘, created algorithmically before being executed via airbrush mounted CNC machinery exemplifies how technology extends our reach into artistic realms previously inaccessible because they demand consistent height velocity, air pressure, needle position etc. – all achievable only through mechanical assistance thereby making these machines extensions of ourselves capable of accomplishing feats beyond our natural abilities

As artists we shouldn’t let tools lead us. Instead we should spend time perfecting those tools according to our own vision.

Tyler Hobbs

This belief resonates clearly throughout Tyler’s carefully crafted works challenging popular assumption that usage of such machinery simplifies or limits artistic creation significantly.

When asked about a large-scale project that remains unrealized due to constraints so far, Tyler mentions the idea of a mural generator algorithm providing instant unique mural painting instructions based on building-side photos. Despite being challenging due to environmental unpredictability requirements public artwork holds great appeal—it offers everyone daily exposure to unobstructed art and provides exciting creative challenges adapting artworks around unexpected building variations. Tyler is resolute in bringing this concept alive one day even while still pondering how best to achieve it.

This was a really interesting art talk with Tyler Hobbs and I encourage you to watch it in full length here:

Hans Ulrich Obrist (born 1968) is a Swiss art curator, critic, and historian of art. He is artistic director at the Serpentine Galleries, London. Obrist is the author of The Interview Project, an extensive ongoing project of interviews. He is also co-editor of the Cahiers d'Art review. Tyler Hobbs (b.1987) is a visual artist from Austin, Texas. His work focuses on computational aesthetics, how they are shaped by the biases of modern computer hardware and software, and how they relate to and interact with the natural world around us. By taking a generative approach to art making, his work also explores the possibilities of creation at scale and the powers of emergence.